Trade and Communications

By Michael Moss

Outwardly the commerce and communications of Glasgow changed little between the wars. There were still two banks with their head offices in Glasgow, the Union Bank of Scotland and the Clydesdale, and two major life assurance offices, Scottish Amicable and Scottish Temperance & General, later Scottish Mutual. The river remained the principal artery of the city with goods continuing to be exported and imported by sea. In 1915 coal exports reached a peak of over 4 million tons and remained at over 2 million tons until 1940. Although plans to build a new dock complex had been laid during the prosperous pre-war years, they were completed during the 1920s with government support and named King George V dock. Remarkably overall trade recovered from its low point in 1920, passing its pre-war peak before 1930. Nevertheless by the early 1950s the coal trade had dwindled to almost nothing and the port was being kept alive by imports of iron ore.

Outwardly the commerce and communications of Glasgow changed little between the wars. There were still two banks with their head offices in Glasgow, the Union Bank of Scotland and the Clydesdale, and two major life assurance offices, Scottish Amicable and Scottish Temperance & General, later Scottish Mutual. The river remained the principal artery of the city with goods continuing to be exported and imported by sea. In 1915 coal exports reached a peak of over 4 million tons and remained at over 2 million tons until 1940. Although plans to build a new dock complex had been laid during the prosperous pre-war years, they were completed during the 1920s with government support and named King George V dock. Remarkably overall trade recovered from its low point in 1920, passing its pre-war peak before 1930. Nevertheless by the early 1950s the coal trade had dwindled to almost nothing and the port was being kept alive by imports of iron ore.

Travel

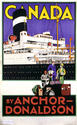

During the 1920s many Scottish families flocked to Yorkhill basin to board Anchor and Donaldson liners to take them to a new life in the United States or one of the British dominions in the largest emigration the country had witnessed. After the slump emigration declined to a trickle with the introduction of quotas by the American and Dominion governments. Nearer to home families still took holidays "doon the watter", going by steamer either from the Broomielaw or the new railway piers at Greenock or Dumbarton. Most people continued to travel to work or for pleasure by tram, train or steamer. Far fewer people than in the south of England owned motor cars and there were few lorries on the city's streets. Buses appeared after the First World War, but were used mostly for excursions and for services between Glasgow and neighbouring towns and villages. It was not until the 1950s that they began to replace the trams on the Glasgow Corporation Transport routes.

During the 1920s many Scottish families flocked to Yorkhill basin to board Anchor and Donaldson liners to take them to a new life in the United States or one of the British dominions in the largest emigration the country had witnessed. After the slump emigration declined to a trickle with the introduction of quotas by the American and Dominion governments. Nearer to home families still took holidays "doon the watter", going by steamer either from the Broomielaw or the new railway piers at Greenock or Dumbarton. Most people continued to travel to work or for pleasure by tram, train or steamer. Far fewer people than in the south of England owned motor cars and there were few lorries on the city's streets. Buses appeared after the First World War, but were used mostly for excursions and for services between Glasgow and neighbouring towns and villages. It was not until the 1950s that they began to replace the trams on the Glasgow Corporation Transport routes.

Banking

The world of commerce was changing and changing fundamentally. Scottish life assurance offices had long since ceased to win the bulk of their business locally but used their reputation for reliability and honest dealing to win custom in England and elsewhere in the world. The Union Bank of Scotland with many industrial customers had to grapple with the serious problems of such well-known companies as Beardmores and Fairfields and looked south and overseas to build its business. In 1920 the Clydesdale was taken over by the London-based Midland Bank and in 1952 the Union Bank of Scotland was absorbed by the Edinburgh-based Bank of Scotland, but on this occasion its name vanished for ever.

The world of commerce was changing and changing fundamentally. Scottish life assurance offices had long since ceased to win the bulk of their business locally but used their reputation for reliability and honest dealing to win custom in England and elsewhere in the world. The Union Bank of Scotland with many industrial customers had to grapple with the serious problems of such well-known companies as Beardmores and Fairfields and looked south and overseas to build its business. In 1920 the Clydesdale was taken over by the London-based Midland Bank and in 1952 the Union Bank of Scotland was absorbed by the Edinburgh-based Bank of Scotland, but on this occasion its name vanished for ever.

An exception was the Savings Bank of Glasgow, the largest in Britain, which provided personal deposit accounts for Glasgow's citizens, but even the Savings Bank had to change its appeal to attract custom. With the introduction of old age pensions and other state benefits, there was less incentive to put money aside for family emergencies and instead people were encouraged to save to buy goods, such as furnishing, or simply to take holidays.

An exception was the Savings Bank of Glasgow, the largest in Britain, which provided personal deposit accounts for Glasgow's citizens, but even the Savings Bank had to change its appeal to attract custom. With the introduction of old age pensions and other state benefits, there was less incentive to put money aside for family emergencies and instead people were encouraged to save to buy goods, such as furnishing, or simply to take holidays.

Mergers and Acquisitions

The acquisition of Glasgow commercial enterprises characterised the period. In 1914 P&O merged with the British India (BI) line, the largest British shipping company which had been established in Glasgow and whose ships were still registered there. Even David MacBrayne & Co, which operated steamers to the West Highlands, was swallowed up the Liverpool-based Coast Lines in 1928. The Anchor Line, which still had its head office in Glasgow, went into liquidation in 1935 and a London-based consortium acquired its assets. The most important shipping company to remain in Glasgow was the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, but even that was destined to disappear after its fleet was scuttled when the Japanese invaded Burma in 1941. The Glasgow & South Western Railway Co lost it independence in 1923 when it became part of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway, which itself was nationalised in 1947. The unmistakable impression was that control of Glasgow's trade and commerce was passing away from the city.

The acquisition of Glasgow commercial enterprises characterised the period. In 1914 P&O merged with the British India (BI) line, the largest British shipping company which had been established in Glasgow and whose ships were still registered there. Even David MacBrayne & Co, which operated steamers to the West Highlands, was swallowed up the Liverpool-based Coast Lines in 1928. The Anchor Line, which still had its head office in Glasgow, went into liquidation in 1935 and a London-based consortium acquired its assets. The most important shipping company to remain in Glasgow was the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, but even that was destined to disappear after its fleet was scuttled when the Japanese invaded Burma in 1941. The Glasgow & South Western Railway Co lost it independence in 1923 when it became part of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway, which itself was nationalised in 1947. The unmistakable impression was that control of Glasgow's trade and commerce was passing away from the city.

Food

With Glasgow still dependent on its own hinterland and imports for its supply of food, there was little incentive for the acquisition of either wholesalers or even retailers. The provision trade continued to be dominated by local firms such as Andrew Clements & Sons and A McLelland & Sons for butter and cheese, Malcolm Campbell for fruit and the mighty Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society, with its headquarters in Glasgow, for everything. Although Massey's chain of grocery shops was taken over by the London-based Home and Colonial Stores in 1930, it continued to trade under its own name. During the inter-war years in keeping with the spirit of the times provision merchants encouraged their customers to buy food produced in the Empire such as New Zealand butter and lamb, South African oranges and Canadian cheese.

With Glasgow still dependent on its own hinterland and imports for its supply of food, there was little incentive for the acquisition of either wholesalers or even retailers. The provision trade continued to be dominated by local firms such as Andrew Clements & Sons and A McLelland & Sons for butter and cheese, Malcolm Campbell for fruit and the mighty Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society, with its headquarters in Glasgow, for everything. Although Massey's chain of grocery shops was taken over by the London-based Home and Colonial Stores in 1930, it continued to trade under its own name. During the inter-war years in keeping with the spirit of the times provision merchants encouraged their customers to buy food produced in the Empire such as New Zealand butter and lamb, South African oranges and Canadian cheese.

Chains and Department Stores

On the whole Glasgow's wholesale and retail warehouses remained fiercely independent, each with their own loyal clientele and niche markets. It was not until the late 1930s that English multiple stores began to penetrate Glasgow. Hugh Fraser, the owner of a family department store in Glasgow, resolved to meet the challenge by taking over stores which might fall prey to an English predator and in so doing laid the foundations of his vast department store empire that would eventually include Harrods.

On the whole Glasgow's wholesale and retail warehouses remained fiercely independent, each with their own loyal clientele and niche markets. It was not until the late 1930s that English multiple stores began to penetrate Glasgow. Hugh Fraser, the owner of a family department store in Glasgow, resolved to meet the challenge by taking over stores which might fall prey to an English predator and in so doing laid the foundations of his vast department store empire that would eventually include Harrods.

Post-War Gloom

During the Second World War food, clothing and many other necessities were rationed and prices fixed throughout the United Kingdom. As a result little appeared to be gained from mergers and acquisitions, except to the far-sighted such as Hugh Fraser, who by 1948 controlled no less than fifteen Scottish department stores. The controls continued long after the war and were not finally abandoned until the 1950s. Thereafter the world of commerce and transport changed rapidly and irrevocably. To most people the rapid run-down of the tramway system was the most tangible symbol of the end of a way of life, much more so than the gradual disappearance of the Clyde steamers. Although the Glasgow of the 1950s had altered little since the outbreak of the First World War, the seeds of the transformation of its trade and commerce had been sown in the intervening years of conflict and depression.